The issue: What sorts of restrictions on speech will be upheld as valid content-neutral time, place or manner regulations?

Although content-based restrictions on speech in the public forum are subject to strict judicial scrutiny (usually a requirement that the restriction serve a compelling state interest and that there is no way of serving the interest that is less speech-restrictive), content-neutral restrictions on speech are subject to only intermediate scrutiny. In general, the government must show that the law serves an important objective (not involving the suppression of speech), that the law is narrowly tailored, and that there remain ample alternative means of communication.

There are, of course, many content-neutral justifications for restricting speech. An anti-leafletting ban helps reduce litter (the Court overturned such a ban in Schneider), a ban on focused picketing outside private homes protects residential privacy (the Court upheld such a ban in Frisby), and a ban on soundtrucks at night helps people get to sleep (the Court upheld such a ban--see also Ward v Rock Against Racism).

Content-neutral justifications for regulating speech are, however, still subject to overbreadth challenges, as demonstrated by the recent case of Watchtower Bible & Tract Society v Stratton (2002). In Watchtower, the Court struck down on an 8 to 1 vote the ordinance of an Ohio town that required all door-to-door advocates of causes, as well as commercial solicitors, to obtain a permit from the mayor's office. The town had attempted to justifiy its ordinance as a fraud-prevention and privacy-protection measure, but Justice Stevens wrote for the Court that the ordinance was "offensive not only to the values protected by the First Amendment, but to the very notion of a free society." The Court found the alleged interests in protecting residential privacy and preventing fraud insufficient to justify such a sweeping restriction. The Court noted that the ordinance reached religious proselyting and anonymous political speech (where fraud is not an issue) and that residential privacy could be adequately protected by another Stratton law that allowed homeowners to place themselves on a "Do Not Solicit" law and then post "no solicitation" signs on their property. The Stratton case strongly suggests that the Court would find a carefully drafted "Do Not Call" law applying to telemarketers to be constitutional.

Two cases concern ordinances, justified on aesthetic and other grounds, prohibiting placement of signs--one on public utility poles and the other in private yards. By a 6 to 3 vote in Taxpayers for Vincent, the Court upholds ban on placing signs on public utility poles. But in City of Ladue v Gilleo, the Court unanimously strikes down the ban on private yard signs, concluding that the ordinance fails to provide ample alternative means of conveying messages.

Finally, McCullen v Coakley (2014) considers the constitutionality of a 35-foot buffer zone around the entrances of reproductive health centers adopted by the Massachusetts legislature. In a unanimous holding, the Supreme Court struck down the Massachusetts law finding that it was not sufficiently narrowly tailored, given the considerable obstacles it presented for anti-abortion protesters in a public forum hoping to engage patients in discussions or to present them with handbills urging that they reconsider their decisions. Writing for a majority of the Court, Chief Justice Roberts did, however, find that the legislation, despite being focused only on speech near reproductive health centers, was content neutral. Justice Scalia objected to the Court's consideration of that issue.

Irv Feiner (NYT, Manny Alban)

In 2002, I received a set of e-mails from Irv Feiner, the defendant in the 1951 U. S. Supreme Court case upholding Feiner's disorderly conduct conviction for a speech he gave attacking President Truman, the American Legion, and oppression of black Americans. In his e-mails, Feiner suggests that a fear of crowd violence was not the real reason he spent 30 days in jail. Click above to read Feiner's emails. (Feiner died in 2009.)

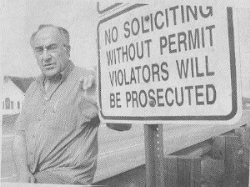

Mayor John Abdalla of Stratton, Ohio, standing by a sign announcing his town's ban on soliciting (and advocating) door-to-door without a permit. (NYT photo)